Yam Kumari Kandel, GPJ Nepal

Hundreds of Nepali Men Are Missing in Ukraine. Their Families Want Answers.

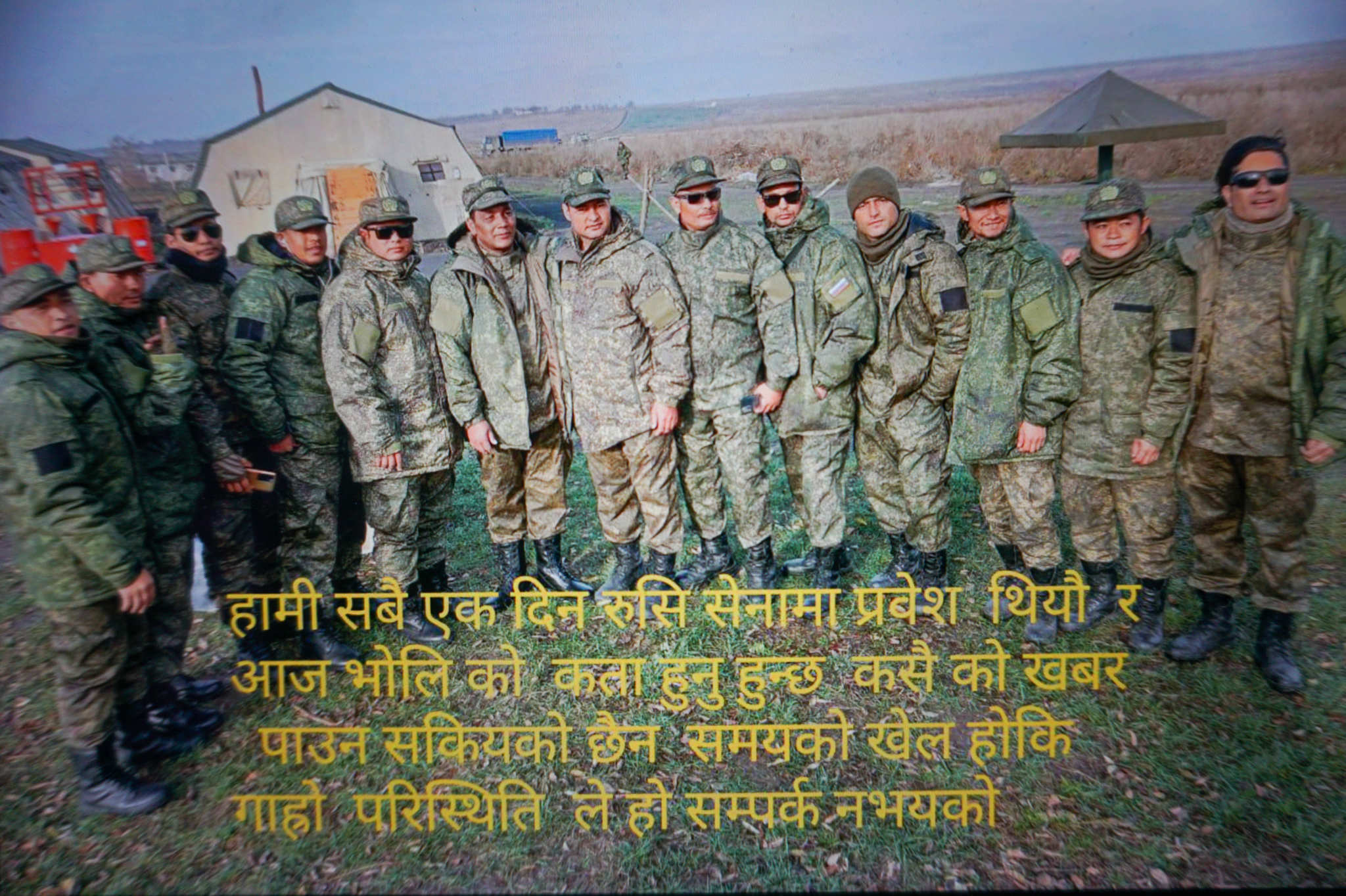

Nepali men serving in the Russian military pose in an image sourced from social media. The text reads, “All of us joined the Russian army on the same day, but now, no one knows where the other person is. Maybe it’s the play of time or maybe it’s due to difficult circumstances that we’ve lost contact.” Hundreds of Nepali citizens have enlisted in Russia’s armed forces, drawn by promises of high salaries and Russian citizenship. While some have returned, many remain unaccounted for.

KATHMANDU, NEPAL — Two years ago, Magar’s husband joined the Russian military to fight in Ukraine, despite having no military experience. He used to work as a driver in Afghanistan and earn 50,000 Nepali rupees (US$366) a month. Russia promised him eight times more than that. When he called to tell Magar, she was shocked — but relieved by what would be a substantial income.

Now, he’s missing.

He hasn’t been in touch since November 2023. Magar, who’d never been to a city, left her village in western Nepal’s Baglung district for Kathmandu to search for information. She hopes to go even farther — to Moscow — to confirm whether he’s dead. If he is, she wants to collect the compensation that the Russian government provides to families of people killed while serving in the military. Magar asked that only her last name be used for fear she’d lose her chance at compensation.

Magar says she’s filed complaints with multiple government agencies — the Department of Consular Services, the Anti-Human Trafficking Bureau, and the National Human Rights Commission. None have provided any information about her husband.

“I want to know if he is alive or dead,” she says.

Now, she’s waiting on government approval to travel to Russia on her own, but officials are withholding approval while they attempt to locate other Nepalis who have gone missing in the conflict. Magar is one among hundreds who say their men disappeared after going to fight for Russia in Ukraine. More than 200 Nepalis have come home from the war, says Leknath Gautam, the acting director of the Department of Consular Services at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but many more are missing. Nepal’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed 70 deaths, over 100 missing persons and at least 343 families who have officially sought government help in finding their loved ones.

Nepal relies heavily on remittances from workers abroad, and the families’ desperate search underscores the deep failures of state accountability and the country’s broken foreign-labor protection system.

“We cannot stop them from going to search for their relatives,” Gautam says. “It is the state’s responsibility to assist them.”

The government says it’s assisting in the search for the Nepali men, but critics argue it has failed to take responsibility, leaving vulnerable families to venture abroad and search alone.

“How can uneducated women from remote areas, who don’t understand the language, culture or geography, search for their loved ones in Russia?” says Kritu Bhandari, opposition leader and member of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Socialist).

‘Survival was impossible’

Currently, 830 Nepali citizens are serving in or have been killed as part of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, says Andriy Yusov, press officer at the Main Directorate of Intelligence in Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense. Thirty-eight, he says, are listed as killed in action, and nine are prisoners of war in Ukraine. The prisoners of war are treated in accordance with international humanitarian law, an official at Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs told Global Press Journal.

Bhandari says the Ukrainian government’s estimates are way off. She manages a WhatsApp group of 3,000 Nepalis involved in the Russian military. Many joined the Russian effort via TikTok, where videos of cheerful Nepali soldiers on the war front attract men who want to become soldiers — and bring home more money than they thought possible. And there’s another temptation: the promise of Russian citizenship for people from other countries who enlist in the Russian military.

On May 16th during peace talks, Russia and Ukraine agreed to exchange 1,000 prisoners of war, the largest prisoner swap of the conflict.

Although the war started in 2022, when Russia encroached onto Ukrainian territory, the number of Nepalis joining the Russian military spiked in 2023. Many, including retired soldiers, students and jobless youth, traveled to Russia on visitor visas and were recruited into the army on arrival. Bhandari says some Nepalis have come home on leave but intend to return.

To slow the exodus, the Nepali government stopped labor approvals for Russia in December 2023. But if men still go, says Dandu Raj Ghimire, spokesperson for the Ministry of Labour, Employment, and Social Security, the government can’t stop them.

International humanitarian law does not prohibit neighboring countries from recruiting soldiers legally. However, Raju Prasad Chapagai, chairperson of Accountability Watch Committee, a human rights organization, says, “If Russia needs Nepali citizens in its army, it must do so diplomatically with Nepal.”

Nepal’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Krishna Prasad Dhakal, says the country has only signed such agreements with the United Kingdom and India.

“If [Nepali citizens] are to be sent safely to a war-torn area for military service, the government must establish a bilateral agreement for their safety and social security,” says Anita Ghimire, director of social research at the Nepal Institute for Social and Environmental Research. “The use of civilians on the front lines during war in another country is not an opportunity, but a tragedy.”

Rural unemployment and economic necessity drive Nepali workers to accept overseas positions that are often ill-defined. Labor migration expert Keshab Basyal says Russia’s recruitment of Nepalis highlights the lack of jobs in Nepal.

“With limited access to education, health care and social security,” he says, “many are driven to risk their lives for a better future.”

Lokesh Shahi, 36, a retired Nepali Army soldier, says he joined the Russian military in September 2023 out of desperation.

“There are no opportunities to earn in Nepal,” he says. “I thought, one day I have to die anyway, so I went to Russia.”

Overseas Support for Russia’s War Effort

-

The Russian army is larger than at the beginning of the war in Ukraine, and it’s still growing. An estimated 30,000 troops per month are being recruited, and recruitment drives have happened in Armenia, Cuba, Nepal and Kazakhstan. More than 11,000 troops have come from North Korea. In addition, people from 44 countries, mostly in Africa and Latin America, work in factories to produce weapons.

Source: United States Senate Armed Services Committee, UK Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Cuba, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crimes

Traveling on a visitor visa, he passed medical exams and was deployed to Luhansk in eastern Ukraine. He was later sent to Kharkiv with a 200-member battalion. He was the only Nepali who survived, he says.

“All I saw were bombs, artillery and dead bodies,” he says. “It felt like survival was impossible.”

Shahi meticulously planned his escape. He contacted the ward office, a local government office in his village in Nepal, and asked for a fake death certificate for his mother. Once he received the certificate, via WhatsApp, he requested leave for the funeral.

Then, Shahi says, he walked 12 days through a forest to reach Luhansk, a city near the Russian border. There, with the help of the Nepal Embassy, he escaped. Back home, he delivered word to the families in his village that their sons, his comrades, had died in combat.

But Magar, and hundreds like her, still lack closure. Many have traveled to Kathmandu for help, and so far, 15 families have flown to Moscow, including seven wives. Some have even rented apartments there. They plan to stay for as long as it takes.

Yam Kumari Kandel is a Global Press Journal Reporter-in-Residence based in Nepal.

Liubov Velychko is a Global Press Journal Reporting Fellow based in Ukraine.